(Entrance to Wieliczka Salt Mine)

We’ve all said it at one time or another: Back to the salt mine. And we all understand the implied, underlying meaning of this ubiquitous phrase: I’m going back to my lousy slog of a job. But does anyone really know why we say it like that, or exactly what working in an actual salt mine might have been like to warrant such a phrase becoming a part of the language?

While touring Poland recently, we visited a salt mine, and not just any old mine but probably the most famous, oldest and largest salt mine in Europe, if not the entire world.

(Going down. That’s a lot of stairs)

The Wieliczka (pronounced vee-yah-LEECH-ka) Salt Mine, located about 25 kilometers south of Krakow in the small village of Wieliczka, encompasses so much history, so much territory beneath the ground, and so much importance to Krakow and Poland, that it’s difficult to state its case without sliding into hyperbole. So I’ll just start with some facts.

Wieliczka Salt Mine is the most visited place in Poland, drawing over 1.2 million visitors per year. It was chosen as one of the 12 original UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1978, back when being part of that list really meant something. It features perhaps the largest preserved collection of original tools and mining equipment in the world, illustrating the development of mining technology from the Middle Ages to modern times.

(Our group ‘down under’)

The mine has been in continuous operation since at least 1290 (the oldest reliable records come from this period) but was probably producing salt even earlier than this. Commercial production was shut down in 2007 due to low prices and flooding in the mine. What little salt still comes out of the mine now is used mostly to craft tourist souvenirs. Constant pumping is needed to keep the water at bay or much of the mine would soon be underwater.

(Endless corridors of timber supports)

Wieliczka reaches a maximum depth of 327 meters – that’s over one thousand feet – and the labyrinthine series of tunnels covers more than 287 kilometers in length. That’s 178 miles. There are more than 2,000 excavation chambers on nine levels, and a seemingly endless succession of corridors, galleries, chambers and even underground lakes.

(Underground lake.You can skip the swimsuit, I think)

It’s little wonder then that non employees, i.e. tourists, are never allowed down in the mine alone under any circumstances. And when you do go down with your guided tour group they do frequent head counts with no stragglers allowed.

(Follow the leader…you don’t want to take a wrong turn down here)

(Statue of St. Kinga getting her ring back…it’s a long story)

The tour route covers 3.5 kilometers or about 2.2 miles, less than two percent of the total area of the mine and lasts about two and a half hours. If you plan on going, wear comfortable walking shoes and bring a jacket as the temperature is always a constant 14-15 degrees Celsius, about 55 F. The tour begins with a descent of a 378 step wooden staircase to the depth of 210 feet underground, but that’s just a start. You go down plenty more from there. The good thing is most of the walking is either on level ground or downhill. Thankfully, at the end there is a lift to take you back to the surface.

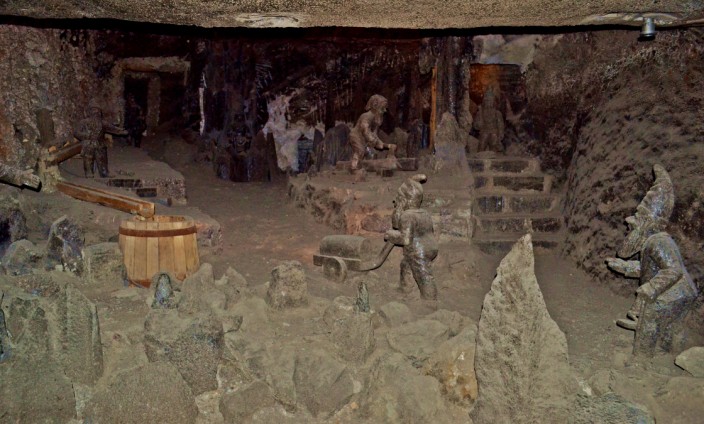

(Diorama illustrating medieval working methods and conditions)

(Another diorama)

It is a fact that there were periods during the Middle Ages when salt was actually more valuable than gold. I don’t have exact figures or dates to back up this claim but that’s what we were told. As you could imagine then, the Wieliczka salt mine was the main factor in making Krakow a major center of trade. Trade routes from every direction of the map, and not only Europe but from Asia and the Middle East, converged here, bringing enormous wealth, power, and influence to Krakow and the burgeoning Polish empire.

(The chapel of St. Kinga)

(The main altar of St. Kinga chapel)

(Salt carving of Leonardo’s Last Supper)

Probably the highlight of the tour is arriving at the Chapel of St. Kinga. You first see it from above and marvel at the size of this underground church whose walls are studded with hand-carved artworks and altars, among them the inevitable statue of Pope John Paul II, a replica of Da Vinci’s Last Supper, and huge chandeliers made from rock salt as well. The floor tiles, the altars, the statues, yes, everything is made of salt. Descending the stairs to the main floor (watch your step, it can be slick) you get about 15 minutes to wander and gape at it all, which for me wasn’t nearly long enough. This chapel is still used today for weddings, banquets and the occasional bigshot political photo op.

(Statue of Pope JP2)

(The salty steps)

(In the great chapel)

So back to that original question I posed at the beginning of this piece. Why do we say “Back to the salt mine,” i.e. equate working in a salt mine with the worst possible kinds of jobs? Historically speaking it’s mostly because of the abysmal working conditions: the heat, the grinding monotony, and the danger involved. And yet, we were told, in the Middle Ages this was considered a good place to work simply because the pay was far above average for the times.

A good illustration of this is that some of the workers were allowed to put in a six hour shift and then spend two hours carving monuments and statues or excavating one of the chapels and get paid for it. As you pass through the tour route one of the most incredible aspects is the vast number of these monuments, statues, and chapels carved right out of the salt. They look exactly like granite, being a dark gray in color rather than the white we would all expect. Scrape a bit off with your fingernail though and taste it. Sure enough, it’s salt. Also if you were to slice off a thin chunk and hold a strong light behind it, you will see it is translucent.

There’s a couple of good reasons why there are so many religious icons and chapels down there: 1, the Poles are very devout Catholics and 2, the mine is a very dangerous place to work. Injury and death were commonplace, so naturally the workers did a lot of praying before, during, and after the job. So why not have a convenient place to worship right there where you work?

(Modern stairway with ancient salt stairway next to it in foreground)

(Statues of the gnomes, believed to steal worker’s tools, generally misbehave and get blamed for everything that went wrong)

One of the biggest dangers came from falls. We saw good examples of this in several locations. Alongside our nice modern, sturdy wooden staircase we could see centuries-old stairs chopped right out of the salt, steep, narrow, winding and without rails or handholds of any kind. There were no handrails because as the workers went up and down these dizzying stairways their hands were full of tools and heavy sacks of salt. Just to make it more challenging, the stairs (along with everything else) were constantly bathed in water, basically turning them into giant slip-and-slides. All it took was one misstep by the guy at the top and he would fall unrestrained, toppling all his fellow workers below him like human bowling pins.

Other common workplace hazards included unrelenting heat up to 130 degrees Fahrenheit, cave-ins, and poisonous gas. One of the actual jobs was being the guy who would crawl into newly excavated chambers with a torch to burn off any residue of flammable gases. This fellow wore a suit of water-soaked burlap and if he was lucky he only got singed a little. If unlucky and the gas level was too high, well, instead of a flash and quick burn-off it was more like kaboom! and a new guy doing that job next day. It’s little wonder that the most monotonous jobs like pushing a grinding wheel in a circle all day were the most coveted. Excruciatingly boring, but relatively safe.

(Soviet era ‘Workers of the World’ type statue)

One of the few health benefits for the miners was the aridity of the salt air. Miners lived longer than the average lifespan of the time primarily due to the benefits of breathing the air down there – well, that is if the cave-ins, floods and explosions didn’t kill you first. To this day the mine still houses a private rehabilitation and wellness complex for those with respiratory illnesses.

(Still going down)

One thing the mine operators recognized early on was the tourism potential. Visitors have been descending into the depths of Wieliczka for centuries, including such luminaries as Polish astronomer Copernicus, German author Goethe, composer Frederic Chopin, future pope John Paul II (Cardinal Karol Wojtyla at the time) and U.S President Bill Clinton.

(Our tour guide, Sebastian)

I have to give a shout out to our guide, a personable young man named Sebastian. He led our group of a dozen people with unfailing good humor, conveyed an enormous amount of information, fantastic historical tidbits and anecdotes, kept us moving along at a good pace without feeling rushed and most importantly, as he joked about several times, he didn’t lose anyone along the way…this time. I can’t imagine doing something like this a couple thousand times, as he has done, saying the same things and answering the same questions and being able to keep it fresh and engaging and interesting. We thought he did a great job and if you’re ever in Krakow and sign up for the Wieliczka tour with City Tours, ask for Sebastian. You’ll be glad you did.

One of my favorite anecdotes actually had nothing to do with the mine itself. As we rode back to Krakow on the bus, Sebastian conducted an informal question and answer session. Someone asked him how many languages he spoke (somewhere between five and eight, I’ve forgotten now) and about how difficult the Polish language is. He laughed and said that he’d heard Polish was recently rated the third hardest language in the world, which he thought a bit harsh but maybe not completely undeserved. For example, he said, compared to their southern neighbors, the Czech language seems very simple to a Pole, while to the Czechs, Polish is ridiculously complex. So Poles think Czechs all sound like children, and Czechs think Poles all sound like idiots.

And speaking of the tour itself, I would recommend paying a little extra and going with an excursion like we did. Three big advantages to doing this. One, your bus trip there and back is included in the price; two, you will be in a much smaller group; three, when you get there you will go straight to the head of the line and go inside with virtually no waiting. You can, of course, find your own way to Wieliczka from Krakow without too much trouble. When you get there you buy your ticket and get in line until they have a large enough group – which could be as many as 35 people – to warrant assigning your group a guide who speaks English. Polish speaking tours go most frequently, English second most, German, French and a few others the least frequently. And while you wait you will be standing outside in the elements, hot, cold, raining or whatever.

(Underground cafe)

(Another chapel in the mine)

Quibbles? Well, a few minor ones maybe. I would have liked more time to linger in the places I wanted to linger (always my top complaint about going with guided groups) such as the Chapel of St. Kinga and a few other spots. And the 70 zloty (about $23) admission price isn’t cheap, but what the hell, you’ve come all the way to Krakow and what are you gonna do, boycott the place because it costs a few bucks? You’re on vacation, live a little. So for me, it goes without saying that if you’re in the Krakow region, you simply can’t pass up an opportunity to visit the Wieliczka Salt Mine. You won’t see anything like it anywhere else, and for me that’s always a top-of-the-list travel recommendation.

Greetings from California! I’m bored to tears at work so

I decided to check out your blog on my iphone during lunch break.

I enjoy the information you provide here and can’t wait to take a look when I get home.

I’m amazed at how quick your blog loaded on my cell phone ..

I’m not even using WIFI, just 3G .. Anyways, great site!

ʜi, I read youг blogs regularly. ϒоur writing style іs witty, keep upp the gߋod ѡork!

Very good pictures, very good place. Greetings from Polish.

Thanks for the comments, Mieke. No, I wouldn’t call it glamorous at all, must be a trick of the light in the photos. Fascinating, yes, one of the highlights of our trip.

Fascinating info – great pictures, good narrative – the place looks almost glamorous, but how could it have been?

Totally fascinating! Never knew, and you have beautiful pictures, as well as informative narrative. Thanks, Greg.

The whole place is a little creepy in some ways, especially if you start thinking about just how far underground you are…

Looks like a really interesting place to visit! The statues look a little creepy though! 😀